Chefs and Restaurants

Project Blackbird: National Spotlight

A year after opening, Blackbird had become an undisputed dining destination for both socialites and food lovers in Chicago. Paul Kahan’s influence was starting to emerge on other restaurant menus around Chicago, and the buzz around Blackbird was loud enough to start to attract the attention of national press.

Regina Schrambling: I was traveling a lot at that time, getting tired and losing interest in eating in a lot of places in America. It was boring. I went to Chicago and ate at Charlie Trotter’s, then returned to check out more restaurants. And wow, there was so much energy and creativity in Chicago.

From Schrambling’s 2001 article in The New York Times Magazine: “Virtually every chef I met credited Paul Kahan with leading the war for independents in a city long known for the extremes of high-end places like Charlie Trotter's, the Dining Room at the Ritz-Carlton and Spiaggia and the gotta-have-a-gimmick outlets developed by Richard Melman's Lettuce Entertain You (Cafe Ba-Ba-Reeba, Big Bowl).”

Schrambling: There was a sense of pride there, like, “We don’t have to pretend to be New York; we’re happy where we are.” The media was dominated by the coasts, but these were people doing something interesting, and didn’t need the spotlight. Charlie Trotter’s was that breeding ground—he set the standard—but people were breaking off. He opened the door for a place like Blackbird, where you get the food but not the frippery. Dazzle me on the plate, but I don’t need the rest.

The experience at lunch that day at Blackbird was one that I remember. It was a beautiful day, the light was beautiful, it was a nice setting, the staff cared so much. And Paul’s original thinking; I still remember the celery soup, and my surprise that you could make something that complex with something so basic. It was like having an experience in a foreign country.

That meal was the light bulb for me. Of the food we ate on that trip, it was the most forward thinking. Paul was part of the beginning of the cerebral chef. He was so articulate. I was so used to chefs who could tell me what was in a dish. For him, how it tasted was important, but more importantly, where it came from, the thought process behind it. It was a different world. You need an articulate chef, a leader. I wasn’t surprised he went on to open other restaurants.

Nancy Silverton: I remember being in Chicago for the restaurant show. One of our salespeople had discovered Blackbird, and came back talking about this new restaurant that was unlike anything else around. I went in for dinner and was won over immediately.

This was before Chicago exploded into the sophisticated food scene. We knew places like Le Francais and the Pump Room, but there wasn’t a contemporary style of restaurant like what they did so beautifully and seamlessly. There was the huge flower arrangement at the front, and the way the tables were set—it felt like it was new and run by people who really had a vision. And the food complemented the design, as it should. It was so professional, but so friendly. I think everything about it was very new to me. It was a sharp contrast to what chefs were doing in L.A. It was the food, of course, but you walk in, and it’s so stylish and so hip. I think Paul certainly brought a voice to the Midwest.

Ellen Malloy: I would get Paul’s menu, and two weeks later the same dish, same description, was on someone else’s menu, at places you wouldn’t have thought would do that. Paul knew people were watching and copying him, but he had this disconnect over why. He was just a dude. He didn’t process the impact he had.

Madia: We worried that guests possibly didn't really get early on that we were making a change, meaning we were going the other way, toward more quality than the status quo. We didn't have the fine dining characteristics honed yet.

Malloy: They were fascinating to me. They never needed to worry about anything, and they constantly worried about everything. They acted like they were on the brink. They were driven by what they thought was different and important.

In 1999, Food & Wine named Kahan one of the 10 best new chefs of the year, an honor that would change his career and solidify Blackbird’s place in Chicago’s dining scene.

Kahan: When I won the Food & Wine award, I was like, “Wow, this is cool,” but I didn't think that it insured our destiny or our success. That's just not my mental makeup. I always think it could be better, there's room for improvement. There's always any number of things that could happen.

One of my favorite stories was when I was in New York for “Best New Chef,” and [Lucques chef/owner] Suzanne Goin and I were sitting in the bus, with the other chefs, driving around Manhattan. Everyone was like, “Oh, we have a 28-course tasting menu, we do this many courses.” I was sitting next to Suzanne, and she says, “Do you have a tasting menu?” I said, “I’ve got a tasting menu: it’s appetizer, entrée and dessert.” We both laughed about that.

Food & Wine named Kahan one of the 10 best new chefs of the year.

Phil Wang: When Paul won the Food & Wine award, he and Donnie came into Daniel for dinner. I hope they had a great meal; Paul’s style at that point was very different from Daniel’s. At the end of the meal, Daniel asked me if I would like to go out into the dining room with him and say hello. Never in my life did I think I could do that. So I got to go out into the dining room with Daniel Boulud to talk to Paul, my mentor, about his meal and about winning the award. It was one of the highlights of my young career.

Madia: That New York trip was, for us, another defining moment for taking casual dining further, for welcoming Paul's sensibility and seasonality, taking service attributes and reformulating them in a casual way. We were going to redefine how we served guests and how we define our concept as fine dining. With that meal at Daniel, and Paul's series of chefs that came and dined in the restaurant, we knew that we had something, but we hadn’t nailed it yet. We didn't know exactly what we had.

Kahan: We still haven't nailed it.

Diarmit: It took me forever to realize that we had one of the best restaurants in the city. I heard all the time, “Can you just relax a little bit?” I always just thought we would go away and in a month it'd be taken away. I was very cautious, very protective.

In 2001, the team got another seal of approval, when the restaurant hosted a special dinner for Julia Child and Emeril Lagasse.

Johnson: Julia Child was one of the people who came in and made me go, “Oh my God.” She was so tall! I had just gotten satellite TV and the cooking shows came on, and I would watch Emeril every night, so when I heard we were doing the event, I couldn’t believe it. Donnie put me at the host stand, so I got to take his coat, and the whole nine yards. And he gave me a signed book, which I loved. My mother still has a picture of herself with Julia, on the shelf in her kitchen; she looks at that picture every single night. That was a thrill.

Julia Child spoke with each employee after her dinner at Blackbird.

Snow: Julia Child asked me, “Do you enjoy what you’re doing?” I said yes. She said, “Well, you just keep on doing it.”

Elissa Narow: We made a Meyer lemon dacquoise, pine nut meringue and pine nut caramel garnish for that event. I remember Julia Child had to come in through the basement and come up the elevator, because it was easier for her to walk down stairs than up them. Paul was like, "If you want to say hi to her, now’s the time. Otherwise, you’ll never get to do this again." But she stayed after the event. She asked every single cook who came up to say hello which part of the menu they worked on. Which was so lovely, because who does that? She was so interested in what you did. It was lovely.

Johnson: She wanted to meet everybody, including the dishwashers, and talk to them. She was so nice.

In 2002, the team received its first award from the James Beard Foundation, for restaurant design, and Kahan was named a finalist for the Best Chef: Midwest award. Still, the partners continued to fear that success was ultimately out of reach.

Malloy: Paul was nationally known—had won Food & Wine, and the legend had already started locally. But they had really big goals. When they sat down with me, they said they wanted to win a James Beard award. I said great—that’s something you do, not something I do. I can coach you and guide you, but being a great chef and a great restaurant is what wins an award.

Madia: I've never really thought, “Oh, we're going to be a success.” I mean, things were going well and then 9/11 hit, and it always felt like we were teetering on the brink. I remember the third year we were open, when we actually started making money. We were in the back with our accountant, and he was talking about how much we were going to owe in taxes. It was like, “How are we going to pay this?”

Malloy: They attribute their success to being humble. To me, that’s complete bullshit. It was because they never believed they could let up. At industry events, Paul would have the table set up, all the food prepped and shipped ahead, so he could make the most of it. I remember one event in New York, [former Gourmet editor] Ruth Reichl was there, and Paul didn’t want her to eat his food off plastic forks. So he sent someone to get real forks for her. Another time they drove chairs from Chicago to New York for an event they were doing there, so it had the right feel.

One day, Paul got the call that the Troisgros chefs were coming for lunch. He was with Mary, driving down Lake Shore Drive, going somewhere. He dropped his plans, went to the restaurant and cooked the food himself. He probably served it himself, too.

They were driven by fear of failure; that’s what it was about for them. They showed up for everything, every fucking day. They made sure they were pushing every day. Every single day.

Kahan: I don't really ever think we've made it, that we're a success. I mean anybody can take money out of the cash register and drive a fancy car that they can't really afford. In the end, I think we're all pretty regular guys. I think that has a lot to do with it.

Malloy: We would have reporters in for dinner. Paul would always walk behind the media person and mouth, “Is the food okay?” People were dying about how good the food was, and he’s asking if it’s edible. He would call me up at home if we didn’t see each other after a dinner and ask if the food was good. I would say, “Are you fucking kidding me? Leave me alone and let me go to sleep.” Paul is very confident about his abilities as a chef, but I remember being taken aback that he didn’t realize or believe how much people respected him, looked up to him.

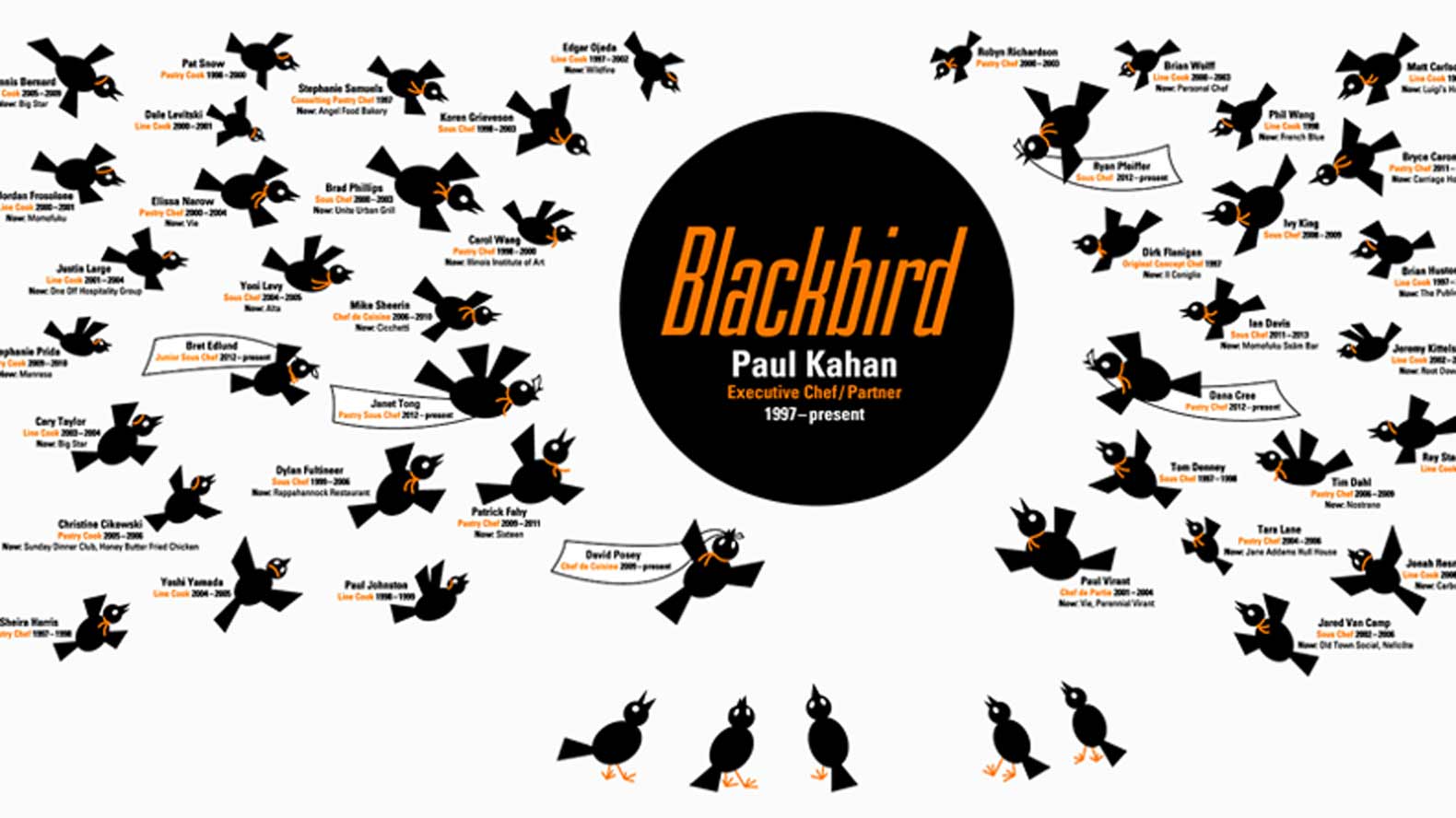

Business continued to boom, and the restaurant thrived with a group of young cooks who would guide its success for a long time, establishing the restaurant as a training ground for some of the city’s biggest talents under Kahan and sous chef Koren Grieveson.

Justin Large: I was in culinary school at CIA and was trying to figure out where to do my externship. I saw a little article about Blackbird and the food they were doing there. It showed a photo of the outside of the restaurant, looking in, and I was immediately drawn to it. I was excited about Paul’s take on food and how ingredient-driven he was. Chicago hadn’t seen—America hadn’t seen—a restaurant like this one.

I called the restaurant one day, and someone put Koren on the phone. At the time, I had no frame of reference of her or her style. I said, “Hey, I sent my resume in, I’m looking to do an externship.” She was super short with me: “Yeah, I burned it.” But we talked and set the dates for me to stage and extern there. It was all of a two-minute conversation. Before I could find out what to bring with me or anything else, she was gone.

Jordan Frosolone: I was working at Coco Pazzo, and went to Blackbird for dinner with my mother and my aunt for my birthday. I remember having a reaction to eating food for the first time in my life; I had to try and stage in that kitchen as soon as possible. The next day I went there and asked if they were looking for anyone. They happened to be looking for a cook, so I trailed a couple of times, then was hired.

It was my first encounter working with people who had made the conscious decision to be cooks and pursue a career in the kitchen. The professionalism, desire and conversations with these young cooks was what I hadn’t seen before. When I worked in other restaurants, it was with guys there to make a paycheck, who didn’t care about food culture, history, food as a whole. It was obvious these people were at a different level than I was at the time.

I was really mesmerized by Paul’s disposition and demeanor: how he carried himself, how he talked to the cooks. I always admired and looked up to him for that. He’s so laid back. He seems to know what he wants and can explain it in a way that other people understand. He was the antithesis of what I expect a chef to be. You expect a dictator, but he wasn’t even close. He was collaborative and shared ideas. And listened to people. I never once heard him raise his voice.

Koren was there all day during prep and service, so she was really the person running daily operations. I had never seen a restaurant where people had that commitment. Koren was the force behind all of those cooks. I was so young and unaware of a lot of my surroundings. The professionalism and desire to execute at a level I had never seen—that was her doing.

Large: Koren and I were station partners for over a year. Koren is one of a kind. They broke the mold when they made her, and I mean that as a compliment. She was definitely the disciplinarian at times. Paul can be stern, but it’s not in his personality to be the bad guy. He would be the good cop to Koren’s bad cop; she had the harder edge. That friction pushed us in a way that brought us a lot of success.

Paul Virant: The first time I ate there was my first meal after my oldest son was born in 2002. I remember I ordered two entrées, and my wife was slightly embarrassed by my gluttony. There was a sturgeon dish with an artichoke barigoule and pickled fennel slaw with clams, maybe with some mayonnaise. It was wood-grilled. I ordered that as a first course, and then I ordered the veal cheeks. There were Peruvian lima beans on it. I still remember a lot of the components, which is pretty amazing. Most of the time I can’t remember details of a dish, but that night everything was right. It was very inspiring.

Former sous chef Koren Grieveson won top awards from Food & Wine and the James Beard Foundation while at Avec.

Brian Wolff: I was cooking at La Sardine, down the street. I went to eat at Blackbird, and I was blown away by it. I really, really wanted to work there. One of our servers was dating a cook there, and he mentioned that there were some people who were leaving Blackbird soon. It seemed like a total stretch, but I thought maybe I could park the cars, they could hire me for something, just to be there. My skills weren’t what you would need to cook at that level.

I went over and checked it out on my day off. Paul suggested I come in to trail. I couldn’t come back for a whole week, and I suggested we do it immediately. I think that impressed him, that I wanted to start that quickly. Brian Huston was leaving to travel, and that was how I tricked them into hiring me. Then I just tried to learn as fast as possible.

I knew right from the beginning I was not in their league. But this place spoke to me; the soulfulness and elegance of the food, the flavors. It just resonated so strongly with me. I wanted it so bad. That was my culinary school; where I learned. People didn’t hoard their knowledge; they supported each other. The other cooks as well as Paul and Koren would take a dish and show you how to make it better. I wouldn’t say I felt it was competitive; it was more supportive. The learning curve was so steep. But it was great. Even just talking with Paul about the amuse for the day was a really good process. I was just trying to keep up.

Koren was so fundamental; I have so much respect for her. She had so much talent, and had so much to teach. She inspired us with her work ethic; nobody worked harder than Koren. She was always there. She was a force in the kitchen. She could do everything better than everyone. She was just so tough, what you’d want from a chef. She had high expectations, but was a great mentor and teacher. She didn’t just tell you how to do something but would get in there and do it herself.

Dylan Fultineer: When I moved to Chicago, Blackbird was the spot. It was the place to be for a young cook. I went there to stage. My stage was very intense. I was coming from a very different market, and had never been in a kitchen like Blackbird’s. I knew it was way above me. I didn’t get a job, but once I realized how many people wanted to work there, I let it go. Cooks were begging for a chance to stage there and work for free. So I bounced around a bit, and later I somehow got the call from Blackbird to work there and was floored.

It was intense. Everything was fabricated in-house, and you had to get to work at 11 a.m. or earlier to get your station ready. There weren’t prep cooks or butchers to help; the line cooks were responsible for everything. You had to get it done, and do it right. Paul is an amazing person, easy to work for in that he was laid back, but you did it over if you messed something up. He had very high standards.

Working with Koren was intense but amazing; she was tough but an amazing cook. She could do everything. I put my head down, kept my mouth shut and followed her lead. She was my mentor.

I was just trying to do my job and survive. You’re surrounded by these cooks who are the best in the city. Everybody had this high regard for cooks at Blackbird. I had a lot of trust and respect to gain. Once you get into it, you’re so busy doing what you’re doing that you miss some of the hype.

We all spent our lives there. If you worked there, that’s all you did. Brian Wolff and I started working there at the same time, so we were close. We would go to the farmer’s market up in Evanston at 5 a.m. on Saturdays to meet with farmers. Brian met his wife at the Evanston market while we were there. In the process, they fixed me up with her sister. So now Brian and I are brothers.

Former line cook Dale Levitski went on to compete on “Top Chef” and open his own restaurant.

Dale Levitski: When I first moved to Chicago, I was working at Deleece, and Paul had just been named a Food & Wine “Best New Chef.” I didn’t know anything about anything, but I kept Blackbird on my radar as a young cook.

Eventually I took a sous chef position at a place called Saucy, a terrible, terrible place. A server there was friends with Koren, and she came in and liked what I did. [Saucy] was a shit show, so I left, and she got me a job at Blackbird.

Getting into Blackbird is one of the best things that’s ever happened in my career. I had cooked at a chain in Iowa, and thought I was a bad ass. I got a job at Blackbird as a lunch grill cook and realized I knew nothing. I walked into that kitchen without any knives. I was that green. I didn’t know I needed my own knives when I walked in there.

I had a lot of work to do to catch up with the other cooks to make it there. Blackbird was about pride, knowledge and skill. You had to compete to be better; we pushed the team to be better. As a team, we could be great, we knew this place was great. It’s a testament to Paul that he put a healthy competitive nature in the staff. It was very positive.

I remember I took a bag of garbanzo beans home, and I was up until 2 a.m. shucking them with Sarah Solomon, one of the best line cooks I’ve ever known. We stayed up so late because it had to be done, and that’s the level of commitment everyone had. Call time was noon or one, but I was there by 10 a.m. because I was so behind. Most days I stood with my back to everyone and listened to everyone talk about food. I became a sponge. I would hear a word I didn’t know, and I would go home and research it. I worked my balls off.

Koren was a lifesaver to me. I could talk to her, and say I don’t know what the fuck I’m doing, and she would teach me and guide me. And Paul was so supportive. At one point he called me the perfect employee, because I always worked and never bitched.

One of the hallmarks of working at Blackbird was the opportunity for any cook to create a dish for the menu.

Wolff: I think Blackbird is really unique in that the opportunity to create a dish was always on the table, and encouraged. If you want to work on a dish, conceive a dish, come in, get the product and work on it. It was scary to do that, to take that leap.

Kahan regularly works with his cooks to tweak dishes for the menu.

Levitski: We would workshop dishes: All the cooks gather around to taste your dish, and tear it apart. It’s Blackbird, so it has to be perfect. One day, Paul put up a dish and asked what we thought. Everyone said, “It’s great,” except me. It was like the scratch on a record. You don’t criticize Paul Kahan. But I was young and stupid. He just looked at me, and asked what I thought. I said, “Well, it’s clunky. It doesn’t read as a Blackbird dish. If you look at everything else on the menu, it doesn’t go with the rest.” Paul looked at me and said, “You’re right.” He will never remember this, but it was huge for me, as a young cook. I was like, I just told one of the best chefs in the country his dish was clunky.

I had heard that Paul wanted a new venison dish. So I came up with a dish, workshopped it on Paul’s day off, then presented it to him and the other cooks. Paul looked at it, then walked away to get Donnie. Everyone was like, “What the fuck?!” Paul always critiques a dish and tears it apart. He tasted it and said, “Great, it’s on the menu Friday.” He didn’t change a thing, not even the garnish. Afterward, the other cooks were shaking my hand, like, “Wow, that was incredible,” and congratulating me. It was the best thing for my confidence. To have a team congratulate you on doing a great job was true team development. There was no jealous slamming of pots and pans; they were proud for me. That feeling is very few and far between in professional kitchens. That was one of the moments in my career I am most proud of.

Carol Wang: I fell in love with the people and the place. Everybody was there on a nightly basis, whether it was Paul, Donnie, Ricky or Eddie. Everyone was so involved, and took so much pride in Blackbird. We saw each other five to six days a week, 14 to 15 hours a day. We fought, we laughed. We were like brothers and sisters. At the end of the day we all had each other’s back.

Narow: They all have different styles and personalities. It probably wouldn’t have evolved to what it is otherwise. A restaurant is never about one person; it’s only as good as all the people in it.

Carol Wang: I remember Paul getting into one of his cleaning fits, and we’d have to break down everything in the middle of service and scrub everything down. That was probably the only time I wanted to strangle him. Something I loved about Donnie was his intensity. I appreciated that and his eye for detail. Ricky was just a big bear, very approachable.

Despite the restaurant’s success, the working conditions weren’t always ideal.

Johnson: There were so many of us in that office. We had a plywood table all the way around the room; it was just a piece of wood on top with two-by-fours holding it up, and maybe a file cabinet underneath. Paul would be in there, making phone calls, calling everybody up and writing down the phone numbers on the plywood. I couldn’t stand the room, it was disgusting in there and I wanted to clean it up. So I went out and bought contact paper, the kind that looked like white and gray marble. I [papered] everybody’s desk and when they walked in and saw it, it was just, whoa, so bright. Paul got so mad at me. I had put contact paper over all of his phone numbers [laughs].

Carol Wang: There were days when the temperature was 103 in the basement, or I would wear a hat, because it was freezing. I used to go up to the kitchen and put my toes on the oven, I was so cold! I loved it when they took over the upstairs space and we moved the pastry department upstairs.

Large: In winter, the basement was great from a food standpoint. You could hang meat down there. You’d go back upstairs to the line and start sweating [laughs].

Despite their success, Kahan and Madia argued a lot, sometimes notoriously, over their relentless perfectionism for the restaurant.

Jared Van Camp: They’re brothers. And they fight like brothers.

Kahan: There were a lot of ups and downs. There were times when Donnie and I were fighting so hard, that I’d ride my bike home from work, sit on my steps, call him up and we’d start the fight over again and yell at each other on the phone for two hours. There were times where he came back to my house, and we started up again. We just had some giant, knockdown, drag-out brawls. There was a ton of growth we had to go through.

Madia: I had six years of therapy; that helped. We figured out after a certain period of time that we were actually on the same side; we were fighting with each other, but we both wanted to reach the same goal. Truth be told, we all want to name the restaurant. We all want to have design influence. We all want to have our name associated with the restaurant. Paul has strong opinions. Ricky has strong opinions. Eddie has strong opinions.

Kahan: We are both super detail oriented; we both have a super firm idea of how we want things to look. And I think we’ve learned to make sacrifices, just like you do in any relationship.

Madia: We have a healthy competitiveness. We want to win at everything. There’s nothing wrong with that. Next

Blackbird Chapters

- Log in or register to post comments